Whatever the reason for the carnage, Pobiner was in disbelief at his discovery. “It was one of those moments when you see something and think: This can’t be,” he says.

In 2017, Pobiner traveled to Kenya to examine dozens of hominin bones housed at the National Museums of Kenya in Nairobi. He was looking for animal bite marks on the bones, which would indicate that early hominins were eaten by African predators such as hyenas or wild cats.

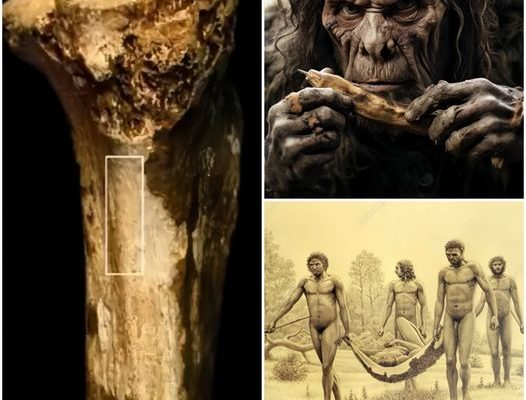

But she found none. Instead, she found what looked like cut marks on a hominid tibia, discovered in 1970 in the Turkana region of northwestern Kenya by the famous British paleoanthropologist Mary Leakey.

Pobiner had seen marks like this before. “I have studied hundreds of fossil bones of animals from the same period and the same region that show butcher marks,” he explains. “So I knew immediately what they were.”

He then made impressions of the cut marks using the material dentists use to make molds of teeth and sent them to his colleague Michael Pante, a paleoanthropologist at Colorado State University and co-author of the new study, without saying what he thought they were.

Pante and Trevor Keevil, a Purdue University anthropology doctoral student and co-author of the study, then took 3-D scans of the mysterious marks and compared them to a database of 898 tooth, butchery and stomp marks made in controlled experiments. Their analysis showed that at least nine of the 11 cut marks had been made with stone tools on the 1.45-million-year-old bone.

There is no reason for such carnage unless the meat is to be eaten, and Pobiner says it appears the diners were trying to separate the meaty calf muscle from the bone. “They are butchering them like other animals are butchered,” he says.

Hominids have been eating hominid meat for more than a million years, and this may be the first evidence of it, says archaeologist and anthropologist James Cole of the University of Brighton in the United Kingdom, who was not involved in the new research.

Until now, the first clear evidence of butchery marks on hominin bones came from the Atapuerca archaeological site in Spain, Cole says. The bones are estimated to be more than 800,000 years old.

But “I don’t see any problem with this behaviour being older,” says Cole, who has studied hominid cannibalism. “It almost certainly was, given the abundance of this practice in the animal world.”

Why these hominins ate each other is a more difficult question to answer. “It’s difficult to discern whether this was nutritional consumption or a more complex cultural activity, such as for ritual purposes,” says paleoanthropologist Michael Petraglia, director of the Australian Centre for Research in Human Evolution at Griffith University in Brisbane, who was not involved in the new study.

However, Pobiner believes this was a case of strictly nutritional cannibalism, or perhaps nutritional anthropophagy, carried out because the butchers needed food. There is no evidence of burials or other ritual behaviour among Homo erectus or other hominins from this time, so it is unlikely they had a ritual approach to eating people, he says.

Cannibalistic rituals may be unique to our species, with some evidence of Paleolithic Homo sapiens remains. More recently, cannibalism was part of Aztec religious beliefs, with strict rules about who could be eaten and who could do so. Even instances of cannibalism for survival, such as at shipwrecks, include stories of ritualized behaviors such as drawing lots.

There is also evidence of cannibalism among Neanderthals, but it appears to have been purely nutritional. “It seems that cannibalism has a more ritualistic cultural aspect in modern humans,” says Pobiner.

Researchers have not ruled out the possibility that the hominid victim was hunted for meat, but it is also possible that it died of other causes and was then eaten. Modern apes, such as chimpanzees, sometimes kill each other in territorial disputes and then eat the dead, Pobiner adds, and they appear to treat the carcasses as a simple source of meat.

“The new research illustrates how much we can learn from previously discovered bones. It shows that new insights into behaviour can be gained from modern observations and the application of novel technologies to older museum collections,” says Petraglia.

“Some of the best discoveries have already been made, but perhaps they have not yet been fully recognized,” Cole adds.

Pobiner also stresses the value of studying ancient fossils with new scientific techniques. “This really underlines the importance of going back and looking at museum collections again,” he says, “because you can find unexpected things.”